People and Ethnics

Green Utopia Tour

Ethiopian People and Ethnics

Ethiopia is truly a Land of discovery with more than 80 different ethnic groups each with its own language, culture, custom and tradition. brilliant and beautiful, secretive, mysterious and extraordinary. Above all things, it is a country of great antiquity, with a culture and traditions dating back more than 3,000 yea rs. The traveler in Ethiopia makes a journey through time, transported by beautiful monuments and the ruins of edifices built long centuries ago. Ethiopia, like many other African countries, is a multi-ethnic state. The differences may be observed in the number of languages spoken – an astonishing 83, falling into four main language groups: Semitic, Cushitic, Omotic and Nilo-Saharan. There are 200 different dialects. Ethiopia also has a rich tradition of both secular and religious music, singing and dancing, and these together constitute an important part of Ethiopian cultural life. It is a country one of the most significant areas of Ethiopian culture is its literature, which is represented predominantly by translations from ancient Greek and Hebrew religious texts into the ancient language Geez, modern Amharic and Tigrigna languages.

Related Attractions

Green Utopia Tour

Konso people

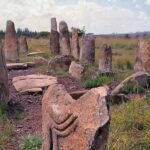

The Konso Cultural Landscape is characterized by extensive dry stone terraces bearing witness to the persistent human struggle to use and harness the hard, dry and rocky environment. The terraces retain the soil from erosion,collect a maximum of water, discharge the excess, and create terraced fields that are used for agriculture. The terraces are the main features of the Konso landscape and the hills are contoured with the dry stone walls, which at places reach up to 5 meters in height.

The walled towns and settlements (paletas) of the Konso Cultural Landscape are located on high plains or hill summits selected for their strategic and defensive advantage. These towns are circled by between one and six rounds of dry stone defensive walls, built of locally available rock. The cultural spaces inside the walled towns, called moras, retain an important and central role in the life of the Konso. Some walled towns have as many as 17 moras. The tradition of erecting generation marking stones called daga-hela, quarried, transported and erected through a ritual process, makes the Konso one of the last megalithic people.

The traditional forests are used as burial places for ritual leaders and for medicinal purposes. Wooden anthropomorphic statues (waka), carved out of a hard wood and mimicking the deceased, are erected as grave markers. Water reservoirs (harda) located in or near these forests, are communally built and are, like the terraces, maintained by very specific communal social and cultural practices.

The Konso Cultural Landscape integrates spectacularly executed dry stone terrace works, which are still actively used by the Konso people, who created them. They bear testimony to the enormous efforts required to use the otherwise hostile environment in an area that covers over 230 square km, an effort which stands as an example of major human achievement.The association between these stone terraces and the fortified towns in their midst are features of an exceptional cultural landscape, which also bears testimony toa living tradition of stele erection. The Konso erect stone steles to commemorate and mark the transfer of responsibility from the older generation to the younger. Konso are among the last stele-erecting people and thus their continuous practice presents an exceptional testimony to an ongoing cultural tradition.

The relation of the stone terraces and the fortified towns of Konso Cultural Landscape, and its highly organized social system, illustrates an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement and land-use, based on common values that have resulted in the creation of the Konso cultural and socio-economic fabric. The dry stone terraces show a sophisticated adaptive strategy to the environment and the labor needed to construct these terraces necessitated a strong cohesion and unified bond among the clans. This interaction with the environment is based on indigenous engineering knowledge and requires traditional work divisions, which are still utilized to consistently perform maintenance and conservation works.

The boundaries of the Konso Cultural Landscape coincide with natural features, like rivers or edges of densely terraced landscape, and are demarcated by the cultural and socio-economic history of the Konso people. All components relevant to the understanding of the traditional system have been included, such as the key tangible attributes of terraces, walled settlements, sacred forests, shrines and burial sites. The clear distinctive character of the landscape is vulnerable to dispersal of the fortified settlements, in case houses are built outside the town walls.

Green Utopia Tour

Hamar people

Hamer also well known as the hamar or hammer are one of the most known tribes inSouthwestern Ethiopia. They inhabit the territory east of the Omo River and have villages in Turmi and Dimeka. They are a semi-nomadic, pastoral people, numbering about 42 000.

Beautiful Hamer woman

Honey collection is their major activity and their cattle is the meaning of their life. They will stay for a few months wherever there is enough grass for grazing, putting up their round huts. When the grass is finished, they will move on to new pasture grounds. This is the way they have been living for generations.Once they hunted, but the wild pigs and small antelope have almost disappeared from the lands in which they live; and until 20 years ago, all ploughing was done by hand with digging sticks.

The land isn’t owned by individuals; it’s free for cultivation and grazing, just as fruit and berries are free for whoever collects them. The Hamar move on when the land is exhausted or overwhelmed by weeds.

Hamer men

Often families will pool their livestock and labour to herd their cattle together. In the dry season, whole families go to live in grazing camps with their herds, where they survive on milk and blood from the cattle. Just as for the other tribes in the valley, cattle and goats are at the heart of Hamar life. They provide the cornerstone of a household’s livelihood; it’s only with cattle and goats to pay as ‘bride wealth’ that a man can marry. A lot of their culture has now become well-known to the outside world. It’s a real privilege to get to Know.

There is a division of labour in terms of sex and age. The women and girls grow crops (the staple is sorghum, alongside beans, maize and pumpkins). They’re also responsible for collecting water, doing the cooking and looking after the children – who start helping the family by herding the goats from around the age of eight. The young men of the village work the crops, defend the herds or go off raiding for livestock from other tribes, while adult men herd the cattle, plough with oxen and raise beehives in acacia trees.

Sometimes, for a task like raising a new roof or getting the harvest in, a woman will invite her neighbours to join her in a work party in return for beer or a meal of goat, specially slaughtered to feed them.

Relations with neighbouring tribes vary. Cattle raids and counter-raids are a constant danger. The Hamar only marry members of their own tribe, but they have nothing against borrowing – songs, hairstyles, even names – from other tribes in the valley.

Green Utopia Tour

Mursi people

The Mursi undergo various rites of passage, educational or disciplinary processes. Lip plates are a well known aspect of the Mursi and Surma, who are probably the last groups in Africa amongst whom it is still the norm for women to wear large pottery, wooden discs, or ‘plates,’ in their lower lips. Girls’ lips are pierced at the age of 15 or 16. Occasionally lip plates are worn to a dance by unmarried women, and increasingly they are worn to attract tourists in order to earn some extra money.

Ceremonial duelling (thagine), a form of ritualised male violence, is a highly valued and popular activity of Mursi men, especially unmarried men, and a key marker of Mursi identity. Age sets are an important political feature, where men are formed into named “age sets” and pass through a number of “age grades” during the course of their lives; married women have the same age grade status as their husbands

Green Utopia Tour

Karo people

The Karo tribe, living in the area southeast of the River Omo in Ethiopia, are a group of just over 1,000 tribespeople. They survive on agriculture and natural annual flooding of the Omo river. They have had the same culture and traditions for 500 years, like traditional dancing and painting their bodies with a mix of ash and fat or water (“Karo Tribe,” 2016)

The Ethiopian government are trying to quickly boost Ethiopia’s economy as it is one of the poorest countries in the world. It needs money and electricity and the Gibe III dam being built on the Omo river would solve this.

Ethiopia relies highly on hydropower for electricity, resulting with construction of dams like Gibe III (Hydrodependency in Africa, n.d.)

Unfortunately the dam then also causes many issues, like threatening 8 different tribes and ecosystem of the river, river banks and Lake Turkana(the lake which the Omo river feeds). Hundreds of thousands of tribes people rely on the annual flooding of the river to feed their crops, but the dam disrupts this creating food and water shortages for the all the Omo river tribes, including the Karo. (Moszyn, 2011) Ethiopian Government Destroying Lives of 100,000’s

The Omo tribes are getting harassed in several ways, homes, food and water supplies destroyed, physically abused and just thrown in jail for disagreeing with the Ethiopian police. The tribes prized possessions and show of wealth are cows, animals essential for wellbeing, are nearly all being taken away by the government as the cows need land. Land which the tribes are getting stripped of (“The Omo Valley,” n.d.) Many companies are indirectly supporting the collapse of the Karo.

Many banks are needed to fund Gibe III for Ethiopia, including the European Investment Bank and the World Bank, as it would cost 1.55 billion Euros to finish. An Italian company called Salini were in charge of building the dam. Surrounding groups and charities convinced some banks that the poorer community, and tribes like the Karo, wouldn’t survive if this was built. In the end, neither the EBI or the African Development Bank decided not to fund this project. (“EIB Pulls,” 2009)

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China however decided to help fund part of the dam anyway, and the World Bank were helping with paying for power lines extracting the energy produced, moving it elsewhere in the country. Many international companies were benefiting from this project, but unfortunately, it has very negative consequences for the Karo. (“EIB Pulls,” 2009)

Contact

- Bole Africa Ave Street.Saay Building 2nd floor

- +251-930-013435

- +251-911-233240

- P.O BOX: 43210 A.A Ethiopia

- marketing@greenutopiatour.com

- info@greenutopiatour.com

Useful Links

Tour Packages

©2023. Green Utopia. All Rights Reserved.